The old man sat cuddled under the flowery duvet, only his head sticking out. At first I was sure the bed was empty and I would have to come back to serve the meal. This wasn’t a typical hospital room and I wasn’t sure where to leave the tray.

“Ah,” a voice with a thick accent came from the bed, “You’ve come to the death room to feed me one of my last meals, have you?”

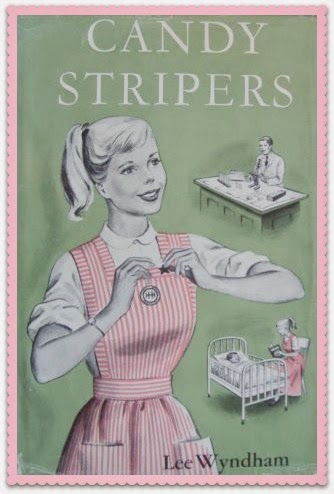

Fifteen years old, I stood in my candystriper outfit, unsure of what to say to the blunt truth. I stood silent for a moment, awkwardly balancing the tray, then kind of coughed and said,

“Is that what they call it?”

“That’s what I call it,” he replied, “But I don’t think my wife is too happy with it…..Come in, let’s see what delicacies you brought to me, today.” I had trouble understanding delicacies because of his hoarse voice and thick accent.

Walking forward, my foot stumbled on a rug; strange for a hospital room.

“There’s a rug in here,” I exclaimed and the man laughed, ending with a rough cough.

“That’s why I call it the death room. they give it to the really sick as their last stop. It’s supposed to be like home but this is nothing like my house- too crowded with furniture and girly.”

I gingerly set the tray of soup and apple sauce with a side of tea on his side table and looked around as he gestured. His bed whirred to an upright sitting position as I gazed around me.

This was my first time in this room.

I’d only started as a candystriper a couple of weeks ago.

Instead of metal side tables, there were dark wood nightstands, maybe saved from a rich lady’s mother’s home at her passing and donated. Nice, but the ornate curlicue carving on the front made it feel dated. A nice big bed in the middle of the two nightstands, queen size I would say, with proper bedding on it. A nice set of sheets and a beautiful flowery blue, burgundy, and white duvet. And that was just the side by the door.

On the other side of the room were centered windows, with a view. To the left of the windows was a huge TV cabinet that matched the nightstands. The cabinet faced the other side of the room where a set of nice couches sat, plump and rose-y beige. There was even an area rug and a coffee table to make it cozier.

Candy-striping had the shortest time commitment per week, fell right after school and was on my route home. A thing decided on out of convenience became something I was good at and even looked forward to.

“Are you ever able to get up and go to the couches so you can watch TV?” I asked as I set up the tray on his lap and helped him get started with the soup. Unwrapping the spoon, I handed it to him and then peeled the lid off of the soup. I raised my eyebrows as if to ask if he could handle it and he gave me the slightest nod.

“No,” he sniffed, “and isn’t it ridiculous that it doesn’t face the bed at all? My family watches it when they come to visit. They visit less and less now.” His brow crumpled in to a set of concerned lines. His silvery-gray hair on either side of his face seemed to be reaching out for help, sticking straight out. He smoothed it as he adjusted his seating position, getting more comfortable to eat. His face was kind, though weary. It looked thinner than it should be but I could see the past- his round face with glad eyes and remnants of smile lines living just under the sick gray pallor of his skin.

“Yeah it seems like a strange set-up.” I replied politely, adjusting my red and white striped apron, hands eventually resting in its pockets. I need to go serve the rest of the meals, but I hate to cut a conversation short. He told me to take a walk around, so I did, stopping to gaze out the window and admired the DVD collection on one of the TV cabinet’s shelves.

“Well, originally it was for mothers who had preemies, difficult births, or sick babies that needed extra time here. They set it up so that the mothers could breastfeed on the couch there or watch TV. Give them a taste of what it’s like to be home with the baby.” The baby came out “ze bobby”.

“Oh that’s fascinating. Do they use it for that now? Well, when you are gone. Not now, now.” I sputtered and then giggled. He laughed, too, which ended in another rough, raspy cough, before replying,

“Oh I don’t know. I think they have found sticking dying people here is a better use for it since most mothers can leave pretty quick but we sick people don’t have a reliable leave-by date.” He laughed again and said, “So that’s why I call it the death room. You know, when the nurses said they would move me somewhere more comfortable and put me in this room, I knew this was it. Last stop.” It came out, “sum-verr murr calm-zort-bull”.

I nodded and said, “I’ll come and visit you more when I come to take your tray away , if you like, but I have to serve the rest of the meals.” He nodded, his blue watery eyes still with a bit of a smile in them and said he would see me soon.

His Gothic gallows humour suited me and we spent quite a bit of time laughing in my short visits. I took extra time to clean his room so that he could keep chatting with me or just be with someone as he drifted in and out of sleep.

I kept him until last and when I came to get his tray, he seemed to be drifting off to sleep. But, as soon as I touched the tray and the plastic spoon made a quiet clatter, he opened his eyes and said,

“Not dead yet!” and patted the bed beside him. I sat, obligingly, and listened to his stories for a few minutes. Stories of living through the Depression, growing up, carving sticks as a boyhood hobby, getting his first job.

He asked me if kids still hung out in forests, climbing trees or riding bikes around the tree trunks in giant zig-zags. I assured him that I did. I told him of climbing trees and realizing I’m scared of heights, making piles of leaves to lay in and stare up at branches, riding my bike down hills (too fast) and grabbing a branch to help me stop, sometimes getting yanked off my bike. He laughed at that last one, saying it was good to take risks. I told him of collecting bugs in a jar to feed and taking photos of tree bark for “research”. He told me of the job “botanist”.

After a few minutes, I realized I was ignoring my other jobs and had to go- so I apologized and said he could take his nap now, with a promise to come back next week.

The other candystriper, Heather, caught up to me in the hall and exclaimed that I ‘was missed and “where were you!” and that I had to do Miss Clark’s bathroom next time because they couldn’t find me and it was time to clean it but she covered for me so hopefully it was all good’, all said in one giant breath. Her eyes stayed full of giggles and her brown Medusa curls bounced up and down as she sped-walked and talked beside me.

Over the next couple of months, I learned of Mr. K’s first job, the first time he felt really scared, how he met his wife, where his kids live, and his favourite place to travel.

The next shift, I visited Mr. K for a couple minutes, making sure it was long enough to chat but not long enough to be missed. Afterward, while changing out of my uniform, I told the other candystripers that I would take that room every time I was on shift, even taking over every bathroom clean there. They replied with a sigh of relief and the exclamation that “only the really sick go in there and it smells like death ALL THE TIME.” They giggled riotously.

I laughed along politely, but told them I didn’t mind and could take it over. Even as a teenage girl, I didn’t understand the constant drama of teenage girls.

Over the weeks, I began to look forward to my visits to Mr. K. I quickly became used to his accent and would have the funniest conversations with him. His Gothic gallows humour suited me and we spent quite a bit of time laughing in my short visits. I took extra time to clean his room so that he could keep chatting with me or just be with someone as he drifted in and out of sleep.

The nurses were told by Mr. K that he looked forward to my visits and began to schedule more time for me to be there. I was relieved of a couple of other rooms and some of the other girls were stuck with more bed turndown services.

Some of the nurses began to see me as a future nurse and made sure I was there to give Mr. K his meds or standing on the sidelines to see the occasional IV be changed. Told I was a calming influence on Mr. K and some of the sicker patients, they would often call on me to be with them in those rooms. Soon, seeing blood, cleaning up vomit after meds didn’t sit well, watching IVs be changed, or needles being given became routine.

And to think, I chose candystriping only after the insistence of my school guidance counselor to add an extra-curricular to my University resume. Candy-striping had the shortest time commitment per week, fell right after school and was on my route home. A thing decided on out of convenience became something I was good at and even looked forward to.

Over the next couple of months, I learned of Mr. K’s first job, the first time he felt really scared, how he met his wife, where his kids live, and his favourite place to travel. I even met his wife on one of her visits and she was just as twinkling and lovely as I expected from her husband’s stories.

Every time I went to Mr. K’s room after grabbing my candystriper schedule, I held my breath a bit. I was relieved when I heard the familiar greeting, “Not dead yet!” and would come in to chat. It started as a jovial shout, raspy but robust: Over time, it became a little softer, less of a declaration, to being whispered laboriously underneath breathing tubes.

It felt silly to cry when I knew from the start that he was on his way out, so to say. It felt silly to cry when I knew he had been in pain but was at peace now.

So, it wasn’t unexpected, but still a shock, when I came into the room one day and the room was empty. Empty in a way I hadn’t felt before. I had lost my grandpa to cancer when I was 8 years old, but he lived two hours away, in the city. My grandpa’s death happened behind the scenes, hidden from my young emotions and not in front of my eyes. I didn’t go to my grandpa’s funeral. This death seemed more visceral, right in front of my eyes, and struck me deeper.

The emptiness of the room was a different kind of empty. The room was emptied of Mr. K’s body, of course, with the bed remade and the duvet stretched tight and thin over the mattress. The nightstands were cleared of his things and the water glass he needed constant sips from; that, too, was gone.

But it was more than that. It felt colder without him here: emptied of soul. The room felt larger and my footsteps seemed to echo when I moved over to the bed to quietly touch the duvet. I walked to the left to check the bathroom in vain for Mr.K, as if he was just dressing to go home- miraculously cured.

When the bathroom was, of course, empty, I imagined a cold wind swirling through the room and shivered. I stared around me. The room felt cold, sterile and empty without him there. I felt a little lost but straightened my shoulders and walked to the nurse’s station.

I didn’t cry.

Not at the hospital and not at home.

It felt silly to cry when I knew from the start that he was on his way out, so to say. It felt silly to cry when I knew he had been in pain but was at peace now. But, I thought, as I walked the hallway to the nurse’s station, ‘Thank goodness they hadn’t filled the room with a new patient yet. That would feel like a violation’.

As soon as the nurse saw me, her eyes got wide and shiny with sympathy. Before I could speak, she said, “I forgot to change your schedule and leave you a note! It happened after your shift last week.” I nodded and had her direct me to my next job, assuring her I was okay. And I was. I didn’t feel like I was going to cry at all. What a strange numbness.

The next week, I came in and was told to go to the main desk. The nurse there told me I had mail and handed me a card. I opened it immediately and a ten dollar bill fluttered to the floor. I left it there as I read the note inside, seeing it signed by Mrs. K as soon as I opened it. Biting my lip, I thanked the nurse, picked up the money, and fled to the bathroom.

I didn’t cry.

I hid in a bathroom stall until I was sure I wasn’t going to cry, for sure, and came out to resume my duties for the night, the card tucked securely in my pocket.

I lost track of the card for awhile and my candystriping days became a distant memory. It wasn’t until my early twenties that I was reunited with the card- finding it in a box that I was unpacking after yet another move.

The unspent money sat safely tucked inside the sweet little card with the yellow flowers on the front. The kind note that Mrs. K wrote was slightly faded, but I could still read it:

“You made his last days more comfortable and full of joy. You gave him something to look forward to and showed a stranger kindness. I am so grateful. Mrs. K”.

I cried.

.

.

.

[…] The Old Man Under The Duvet: A Memory […]